In November I was part of an event held at the Enitharmon Bookshop for the Being Human Festival, Being Writers: A Collaborative Conversation. The evening centred around conversations on the relationship between creative and academic writing. The fabulous Enitharmon poets Hilary Davies and Nancy Campbell were interviewed by myself and another research student from UCL, Jess Cotton, on subjects as diverse as the environment, spirituality, translation, and poetry’s role in communicating history. We wrote a blog post reflecting on our insights from the evening for the Being Human festival website. A slightly expanded version of my thoughts can be found below.

On the back of Hilary Davies’ third poetry collection, Imperium, the blurb-writer claims that in her poetry Hilary ‘draws from her historical sequences a rich, invigorating music.’ But how exactly can we take our research and make the sources sing? And can the poetic process of researching and writing teach academics anything about their own writing practice?

As I began to read Hilary Davies’ poetry, both the collections I found in the Southbank Poetry Library and the glimpses she sent me of sequences from her forthcoming book, I discovered a richness of historical detail and cultural reference that offered an immediate response to the concerns of the Enitharmon event. Hilary is a poet for whom research is an essential part of the writing process.

Hilary Davies’ poetry struck a chord with me, partly because of our mutual love for the twentieth century poet and artist David Jones, but also because her work spoke to a recent concern of my research: that is, the relationship between poetry and scholarship. After a summer spent in the archives of the National Library of Wales, reading the notes made in the margins of David Jones’ collection of scholarly resources and curiosities, I had been thinking a lot about how poetry might perform contemporary scholarship and creatively rewrite it. But the question I had failed to articulate before the event was what role subjectivity might play in this transformation of scholarly knowledge, and whether this subjectivity can ever be critically productive.

Denise Levertov writes of an ‘authentic source of myth in poetry [… where] scholarly knowledge is deeply imbedded in the imaginative life of the writer’ so that it becomes ‘an extension of intuitive knowledge.’ During my conversation with Hilary I was interested in unpicking the threads that had woven meticulously researched detail (like the recent archaeology reports that Hilary said informed one of her sequences, so that her poetry actually became more current than the current scholarship) together with Levertov’s ideal of an ‘intuitive knowledge’ gathered over a lifetime of reading and experience. What is the relationship, for example, between the actually loved and known of Hilary’s Catholicism, and the research required to write a sequence of poems based on the liturgical hours, or the story of Heloise and Abelard?

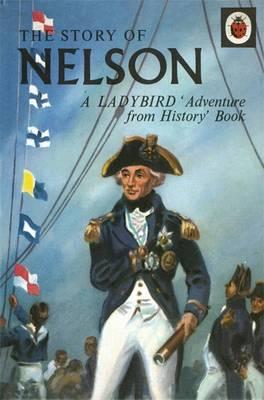

In his ‘Preface’ to his long Modernist poem The Anathemata, David Jones wonders ‘what may be owing’ to, amongst other things: ‘a small textbook on botany, a child’s picture-book of prehistoric fauna, the text of a guide to a collection of Welsh samplers and embroideries, or a catalogue of English china or plate;’ presenting us with a treasure-hoard of bound papers whose influence may be so obscure as to be untraceable. For Hilary Davies one such piece of treasured ephemera might be the Ladybird ‘Adventures from History,’ The Story of Nelson, a book that she described as having ignited her childhood passion for Nelson, Napoleon, naval history, and the frequent pilgrimages she made as a child from her home in Southwark to Greenwich. Its influence on the two historical sequences in her third collection, ‘Imperium’ and ‘Southwark,’ may be invisible to the eyes and ears of her readers, but beneath the surface-weave this childhood reading still resonates.

The conversation with Hilary made me recognise the complexity of this entangled relationship between research and our own personal experiences. In her poem ‘Faultlines’ Hilary writes: ‘the river banks/ we’ve walked ravel backwards in the night,/ Like lost highways.’ How much of ourselves ends up in our research? Perhaps like the lost highways of ‘Faultlines’ our readings are steps that can never be completely retraced; this doesn’t mean that we never made the journey.